Article by: Hari Yellina (Orchard Tech)

According to official reports, 2021 was truly an exciting year for Australian farmers. Climate change had previously been a source of uncertainty, and possibly apprehension, for the regions. Moreover, until a few months ago neither the federal government nor opposition had set out a clear plan for the future of farmers. However, in 2021, Aussie officials were forced to change tactics. The EU threatened a carbon tax on imports from high-emitting countries like Australia, and a major international climate conference turned up the diplomatic heat. The plans that emerged from these discussions emphasise carbon offsets as a crucial tool for reducing emissions, and the land Australian farmers are sitting on could help them cash in.

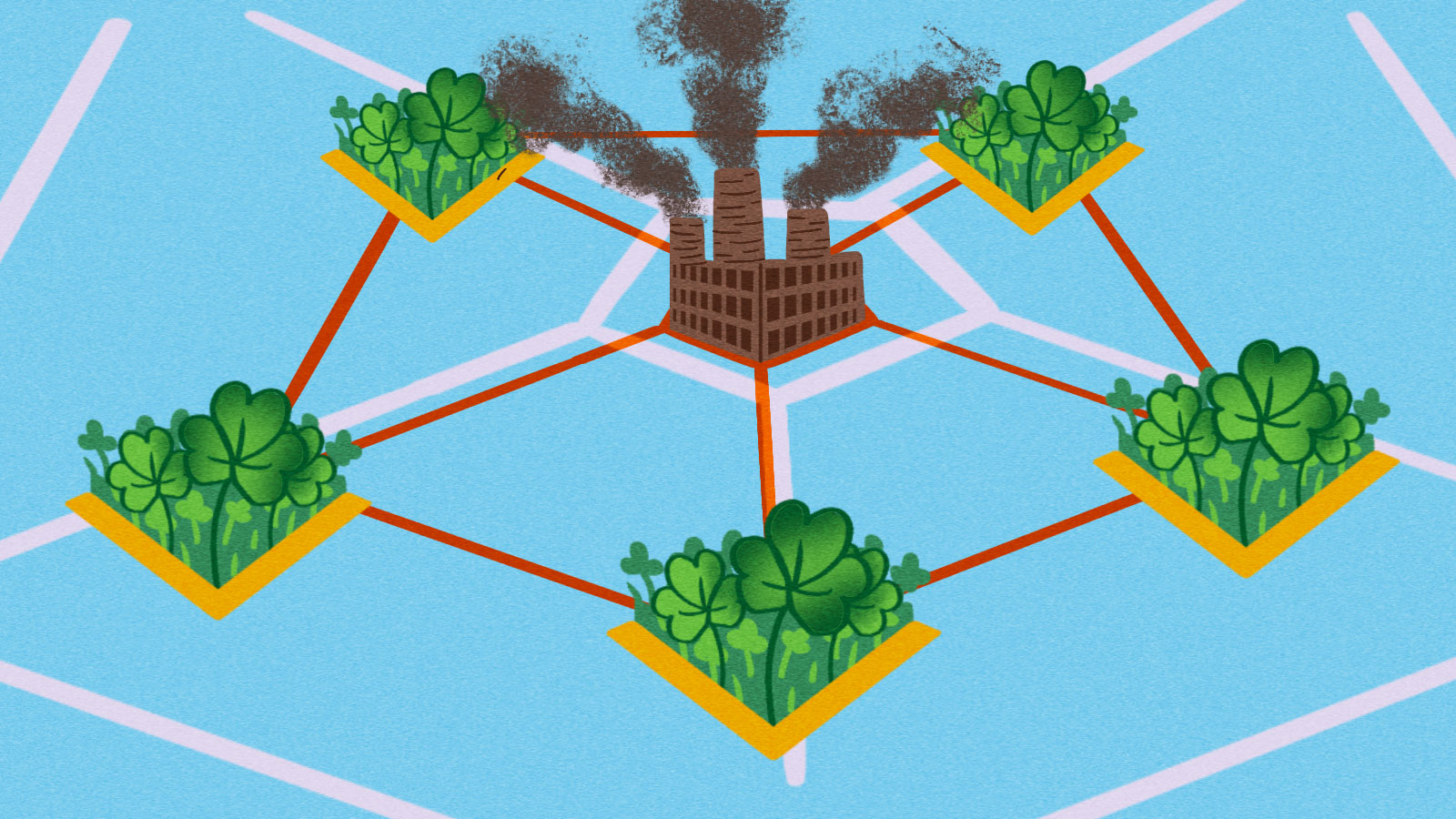

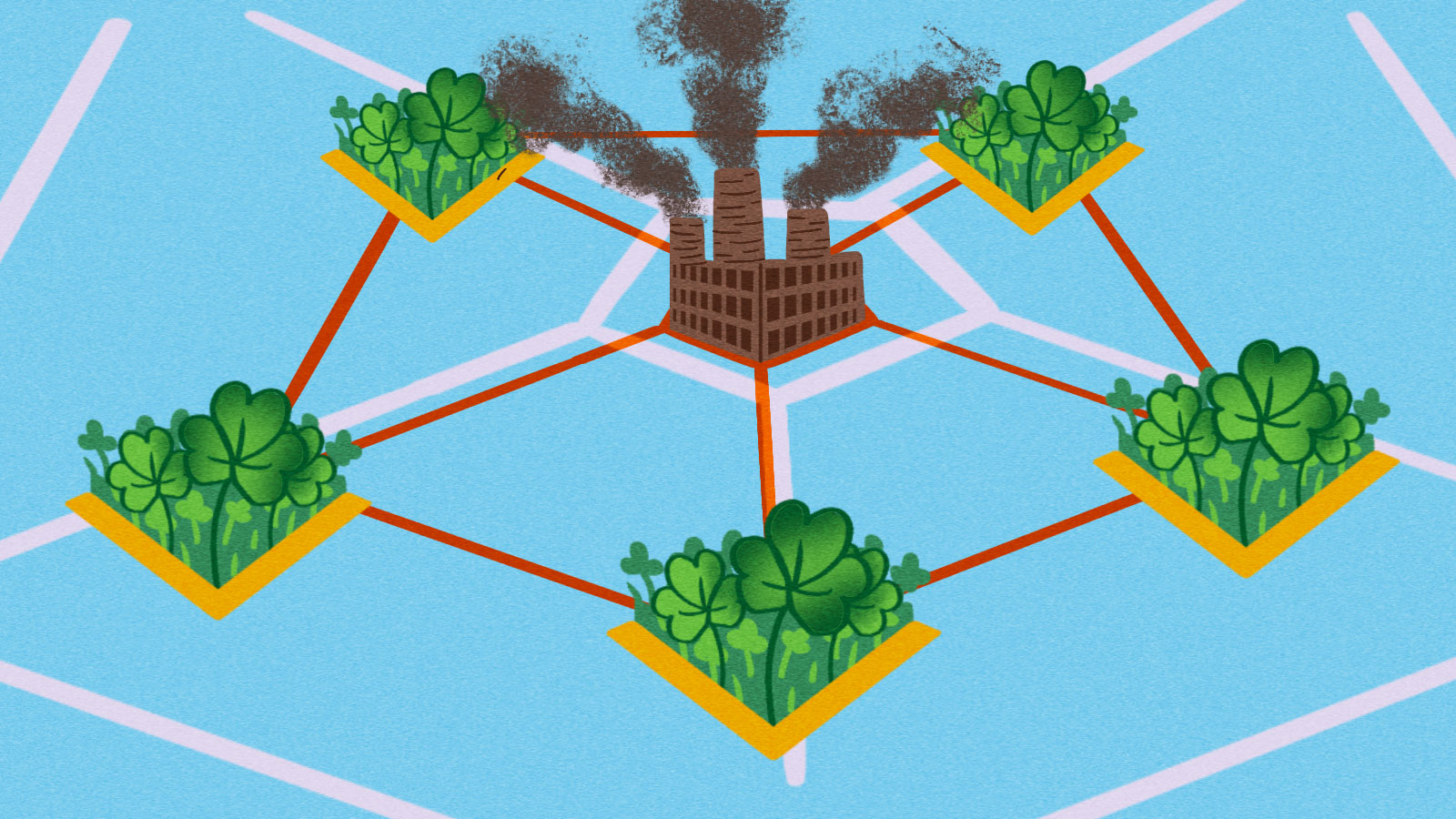

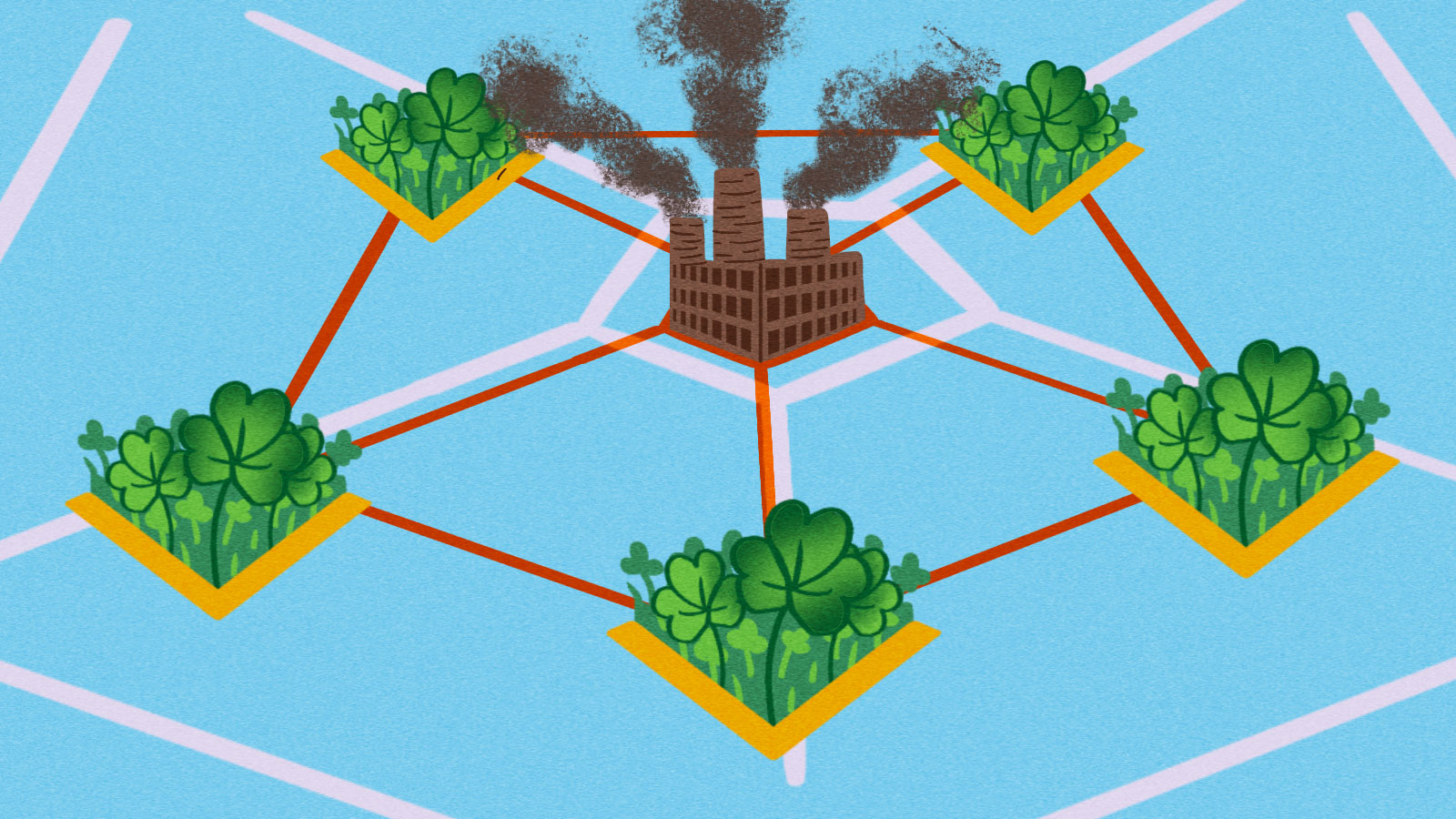

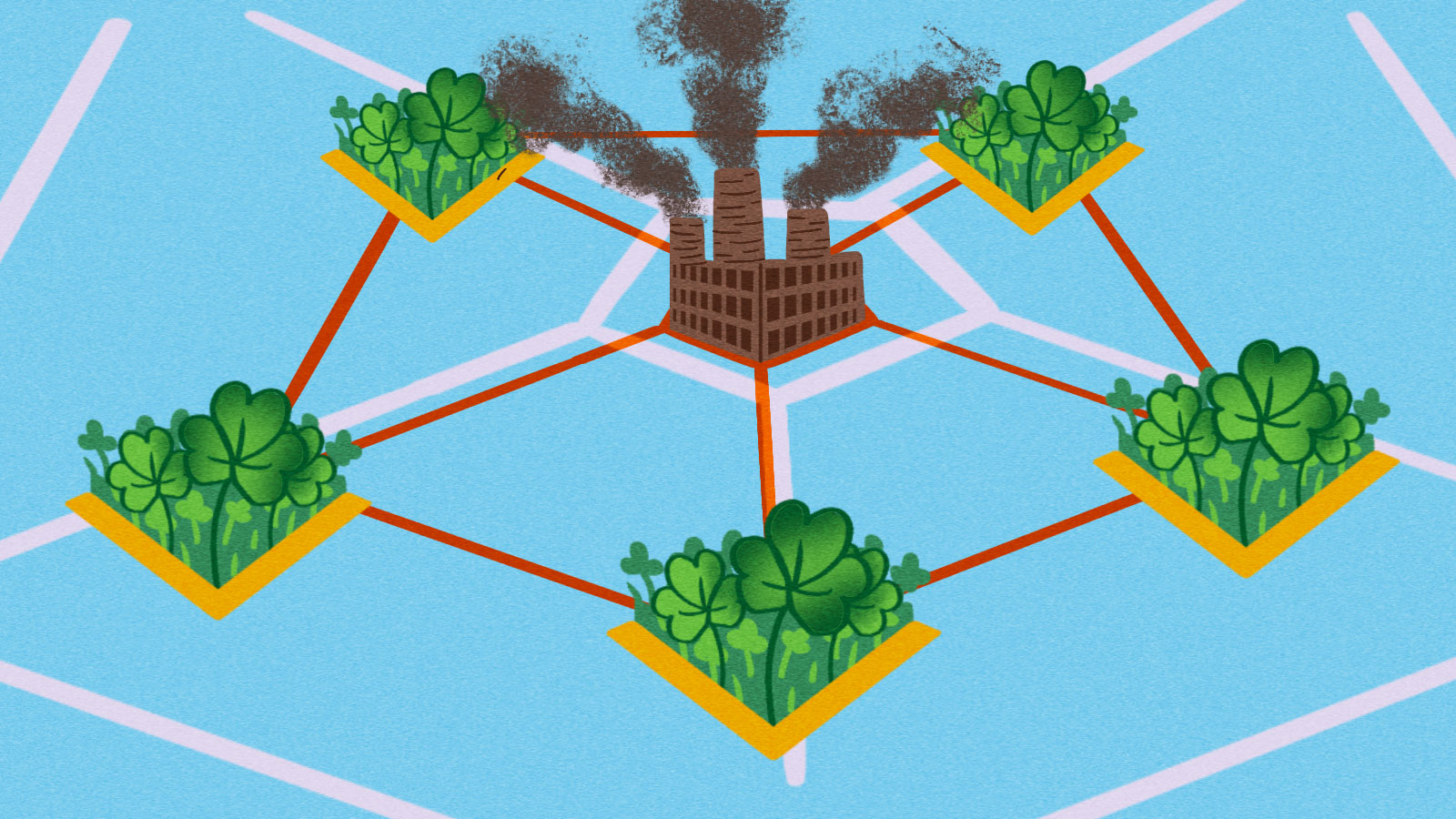

Farmers can generate offsets, called Australian Carbon Credit Units, by abating or sequestering carbon on their land. These credits can either be sold to the federal government or can be purchased in the secondary market by corporates that need to meet regulatory requirements or are simply keen to flash green credentials. With the price in the secondary market more than doubling to $47 this year, carbon credits are becoming an increasingly lucrative source of revenue for Australia’s regional landholders.

Currently, “human-induced regeneration” – leaving a parcel of land alone to let natural regrowth take over – is the most economical way to earn ACCUs within the agriculture sector. Nevertheless, higher prices could also make planting trees, or sequestering carbon within the soil, financially attractive options. The two major parties recently released competing climate plans that might unlock these revenue opportunities.

The government’s net-zero modelling expects new revenues will flow to regional landholders. Their plan assumes that Australia make it to net zero through a combination of heroic technology breakthroughs and cheap offsets purchased from farmers. Under this modelling, Australian landholders reap $5bn a year, equivalent to the current value of our lamb industry. Labor’s counter-proposal leans even more heavily on the proven capabilities of Australian farmers to sequester carbon. Labor’s Safeguard Mechanism cap, which sets a limit on unabated emissions for major polluters, will be tightened yearly, providing more clarity over revenue for carbon farmers.

Yet, somewhat surprisingly, one of the biggest threats to this boom in revenue for Australian farmers is the National Party. Its fear that productive agricultural land may be used for carbon farming has led to obstructive policies that harm landowners’ interests. The Nationals fought to limit farmers’ rights to use their land to generate ACCUs. Under a recent agreement, no more than one-third of any farm’s land could be used for carbon abatement and sequestration – even if doing so would mean greater revenue for Australia’s regions. But farmers are best placed to decide what to do with their land and should be given the freedom to do so. Many are choosing to use a portion of their land to earn ACCUs – it can turn unproductive farmland into a valuable source of drought-resistant revenue. The Nationals are also refusing to budge on 2030 targets, despite the fact that more ambitious emission reduction goals would spur demand for ACCUs and mean greater opportunities for Australian farmers.